“What was Reconstruction?” James Loewen asked a class of incoming freshmen at Tougaloo University, a predominantly Black school in Mississippi in 1970. What he heard from them he calls “the Confederate myth of Reconstruction.” His paraphrase:

Reconstruction was the time when African Americans took over the governing of the Southern states, including Mississippi. But they were too soon out of slavery, so they messed up and reigned corruptly, and Whites had to take back control of the state governments (157)

I attended high school in the north in the early sixties and I recall much the same story. John F. Kennedy told a similar story of L.Q.C. Lamar in the Pulitzer-Prize-winning book Profiles in Courage. The American Library Association’s favorite book of all time Gone with the Wind described the empowered slaves this way: “Like monkeys or small children turned loose among treasured objects whose value is beyond their comprehension, they ran wild—either from perverse pleasure or simply because of their ignorance.” Another version of the Confederate myth of Reconstruction.

Answering the misconceptions of his students in 1970, Loewen countered:

- Regarding control–all governors were white; almost all state legislatures had white majorities

- Regarding corruption– “Mississippi enjoyed less corrupt government during the Reconstruction than in the decades immediately afterward” (157)

- Regarding restored control by whites: some White Democrats used force and fraud to wrest control from biracial Republican coalitions.

Loewen was glad to report that twenty-five years later the majority of American history textbooks portrayed the Reconstruction more objectively. The Triumph of the American Nation (1986) explained that: “The southern Reconstruction legislatures started many and needed overdue public improvements . . . strengthened public education . . . spread the tax burden more equitably . . . [and] introduced overdue reforms of in local government and the judicial system” (157).

The horrors of the treatment of African Americans after the Civil War are only beginning to be explored.

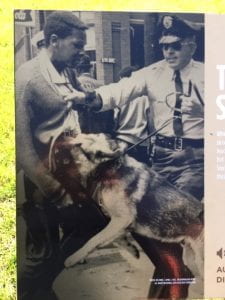

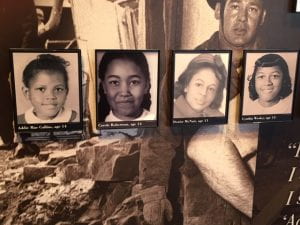

. “More than 4400 African  American men, women, and children were hanged, burned alive, shot, drowned, and beaten to death by white mobs between 1877 and 1950.” The public record of these atrocities has come to light through the Memorial for Peace and Justice, which displays them by hanging pillars by name and county. Bryan Stevenson, who organized the research and construction for the monument, believed it would serve as a kind of Holocaust Museum for viewing the terror of lynching. Defining characteristics of lynching is that it be public and it go unpunished. Lynching was actually a spectacle sometimes attended by hundreds with celebration and picnicking. It was indeed a form of terror, punishing Blacks for incidental offenses like forgetting to say “sir” or looking a white woman in the eye.

American men, women, and children were hanged, burned alive, shot, drowned, and beaten to death by white mobs between 1877 and 1950.” The public record of these atrocities has come to light through the Memorial for Peace and Justice, which displays them by hanging pillars by name and county. Bryan Stevenson, who organized the research and construction for the monument, believed it would serve as a kind of Holocaust Museum for viewing the terror of lynching. Defining characteristics of lynching is that it be public and it go unpunished. Lynching was actually a spectacle sometimes attended by hundreds with celebration and picnicking. It was indeed a form of terror, punishing Blacks for incidental offenses like forgetting to say “sir” or looking a white woman in the eye.

Although the Freedman Schools became a hallmark of education for former slaves, they were under continual assault. The head of the Freedman’s Bureau reported “In 1865, 1866 and 1867 mobs of the baser classes at intervals and in all parts of the South occasionally burned school buildings and churches used as schools, flogged teachers or drove them way, and in a number of instances murdered them.” (160). The threat of an educated black citizen seemed like the threshold to voting and sitting on juries, empowering actions.

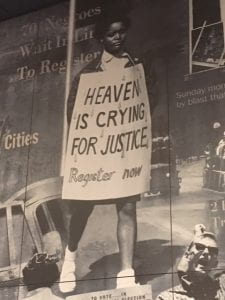

Voting was the seat of power and the final victim of white supremacy in the Reconstruction. In spite of the 13th and 14th Amendments, the state legislatures of every Southern and border state disenfranchised the vast majority of Black voters between 1890 and 1907. While the right to vote was guaranteed by the U.S. Constitution, the enforcement of that right has been problematic from the Reconstruction till today. Much of the blood of the Civil Rights Movement was shed to regain this right for all citizens.

Even after the Voting Rights Act of 1965 civil rights crusaders remain at war with a prohibitive system. As I write today unknown numbers of citizens of Atlanta had to abandon their place in line because of inadequate numbers of polling places and failure of new voting equipment. Such problems bedevil urban centers with high concentrations of back citizens.

If you keep alert today you will find numerous opportunities to re-learn the Reconstruction. PBS just finished broadcasting a three-hour series featuring reputable historians setting the record straight. (https://www.pbs.org/show/reconstruction-america-after-civil-war/)

The need to change the narrative of human rights begins with the historical narrative. Until we revisit the Reconstruction, many of us don’t know what we don’t know.