Put on the whole armor of God, so that you may stand against the wiles of the devil. (Ephesians 6:11)

I wanted to clarify something about this verse invoked by Kari Lake. She may not know the context of the verse, but if she does know, then shame on her.

On April 14 in Lake Havasu City, Arizona, Kari Lake, candidate for U.S. Senator said

We’re going to strap on our seatbelt. We’re going to put on our helmet — or your Kari Lake ball cap. We are going to put on the armor of God. And maybe strap on a Glock on the side of us just in case. https://www.nytimes.com/2024/04/16/us/politics/kari-lake-glock.html#:~:text=%E2%80%9CWe’re%20going%20to%20strap,of%20us%20just%20in%20case.%E2%80%9D

For our struggle is not against enemies of blood and flesh, but against the rulers, against the authorities, against the cosmic powers of this present darkness, against spiritual forces of evil in the heavenly places. (Ephesians 6:13)

The “rulers. . . the authorities . . .the cosmic powers” in these verses refer to spiritual enemies, not physical ones, not campaign rivals. The Apostle Paul believed that the world was fraught with spiritual forces that induced fear, prejudice, rage, deceit in people who opened themselves up to manipulation: the way we may find ourselves doing something in a mob that we would never do individually. If you have seen the rising rage of crowds, you might get the sense that Paul knew what he was talking about.

When someone talks about the “armor of God” and then says in the next sentence, . . . And maybe strap on a Glock on the side of us just in case, that is an offensive misuse of scripture in order to excite a crowd and pay homage to gun rights. In fact inciting a crowd is the surest way to bring the “cosmic powers of this present darkness” onto the set. Remember what happened when Donald Trump said, “We fight like hell. And if you don’t fight like hell, you’re not going to have a country anymore” on January 6. That was the closest example I can remember of stirring up the spiritual forces that emerge from crowd behavior. The results speak for themselves.

I’ll call it “Bible burping,” the tactic of burping up scripture to punctuate political speech just the way a barfly burps up beer to punctuate his (or her) opinions. The medium is the message. Burping is the medium; the message is “pay attention.”

During the 2016 campaign, Donald Trump, asked about his favorite Bible verse, said “I mean, you know, when we get into the Bible, I think many. So many,” he responded. “And some people—look, an eye for an eye, you can almost say that. ”

About this passage in Leviticus (“an eye for an eye”), Jesus said:” Ye have heard that it hath been said, An eye for an eye, and a tooth for a tooth: But I say unto you, that ye resist not evil: but whosoever shall smite thee on thy right cheek, turn to him the other also.” (Matthew 6:38). It’s funny how no one in a political campaign quotes that verse.

The Bible, both the Hebrew and the Christian scriptures, has always been important to me; I am apt to quote it in my own discourse about politics or religion. I try to avoid taking the language out of context to make my point. The weaponizing of the Bible offends me, because it turns something sacred into something calculated for damage. When politicians use scripture out of context to stir anger in voters, they are doing the devil’s work. I am not sure if I mean a real entity or an inflammatory spirit, but the results are the same: delirious audiences.

If you recognize it, the weaponizing of scripture, call it out. It doesn’t matter who does it, Republican or Democrat or Third Party candidate. It is wrong to quote the Bible out of context for manipulation or campaigning for power. It is wrong to Bible burp, to quote fragments to arouse a crowd.

Shakespeare said it best:

The devil can cite Scripture for his purpose.

An evil soul producing holy witness

Is like a villain with a smiling cheek,

A goodly apple rotten at the heart:

O, what a goodly outside falsehood hath!

Merchant of Venice (I, iii, 98-103)

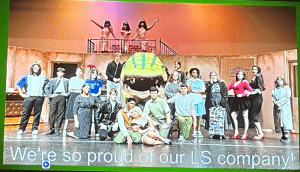

What about the latest rendition, just finishing a run in the Cincinnati suburb of Finneytown? This version offers more of the sinister take-over of Audrey, but her offspring appear as the familiar main characters sporting the flowery coronas around their heads. Everyone seems delighted with the absurd invasion of Audrey’s descendants.

What about the latest rendition, just finishing a run in the Cincinnati suburb of Finneytown? This version offers more of the sinister take-over of Audrey, but her offspring appear as the familiar main characters sporting the flowery coronas around their heads. Everyone seems delighted with the absurd invasion of Audrey’s descendants.