The St. Louis 1904 World’s Fair was billed as the celebration of the one hundredth anniversary of the Louisiana Purchase. Launched in the summer of 1904, the Fair brought in 20 million visitors over seven months. Walter Johnson lists the highlights in some detail, including dozens of babies living in incubators and rotated into cribs, a nine-acre reconstruction of the Tyrolean Alps, and an eleven-acre reconstruction of the Holy Land. On the grounds of Washington University the 1904 Olympics took place “as a sort of sideshow,” remarks Johnson. [The Broken Heart of America: St. Louis and the Violent History of the United States.

Among the featured scholars and scientists at the fair were Frederick Winslow Taylor (“time management”), the German sociologist Ferdinand Tonnies (society vs. community), and the historian Frederick Jackson Turner (“frontier thesis”). As Johnson sees it, however, it was anthropology that framed the message. Frederick Skiff, the manager of the exhibits, said they were “registering not only the culture of the world at the time, but indicating the particular plans along with which different races and different people may safely proceed, or, in fact, have begun to advance towards a still higher development” (204).

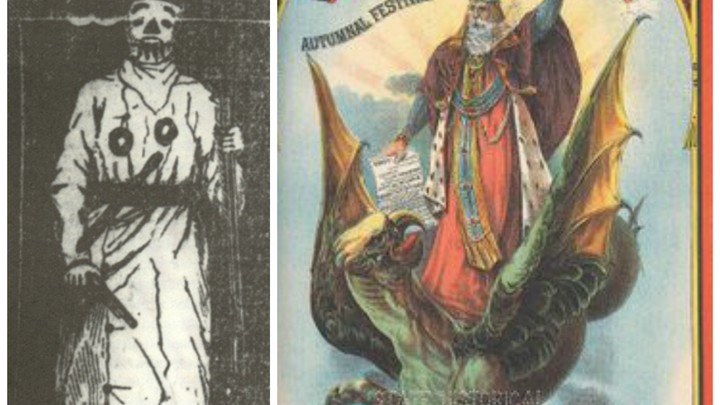

In what Johnson describes as a “human zoo,” ten thousand people were exhibited in reconstructions of their “native habitat, including:

- Ainu people from Japan

- “Patagonians: from the Andes

- 51 of the First Nations of North America, including

- Chief Joseph of the massacred Nez Perce

- Quanah Parker, the Comanche soldier

- Geronimo, the Apache chief, posing for 5 cent-photographs with white leaders and

- playing the part of the Sitting Bull in daily reenactments of the Battle of Little Bighorn

- Ota Benga, one of seven other people sold to Samuel Verner as Mbuti “pygmies” from the Congo Free State

- exhibited at the Fair as a “cannibal”

- danced with other enslaved Africans for as many as 20,000 people at a time

- later exhibited in a cage at the Bronx Zoo

- in March 1966 built a fire, danced, then shot himself through the heart in Lynchburg, VA

The exhibits were intended to represent a “march of human progress,” placing the savages of the Congo at one end and white humanity at the other. As Walter Benjamin wrote fifty years later, “There is no document of civilization that is not at the same time a document of barbarism” (“Theses on the Philosophy of History,” in Illuminations, ed. Hannah Arendt (New York: Schocken Books, 1969), no. 7.

Although the United States had concluded the war in the Philippines in 1902, American troops were still fighting insurgents in 1904. Despite the conflict, the U.S. War Department transported one thousand Filipinos and 400 additional Philippine Scouts, U.S. aligned soldiers, to the most-visited exhibit at the Fair, the “Philippine Reservation.” William Howard Taft, the US military governor of the Philippines argued that the Fair would exert ” a very great influence on the pacification of the Philippines” by influencing the Filipinos through the exhibit of the wonders of modern civilization and reconciling them to their fate as conquered people. Johnson called the Philippine Reservation a “civilizationist psyop, an act of psychological warfare.”

Within the Reservation the tribes were assigned different levels of civilization:

- the Visayans – “intelligent”

- Islamic Moros – “fierce”

- Bagobo – “savage”

- Negritos – “monkey-like”

- Igorots – “picturesque”

The near-nudity of the Igorot made for controversy and fascination at the Fair. Some worried that the naked dark bodies might horrify or stimulate the white women attending the Fair. Government officials thought they would undermine the case that the US was civilizing the Filipinos. The Anthropology Department thought they should represent the authentic culture of their tribe. President Theodore Roosevelt settled the debacle by requiring codpieces worn in strategic areas to create the impression of both the primitive and the civilized.

According to the leader of the Fair’s Anthropology Department, William McGee, “There is a course of progress running from lower to higher humanity, and all the physical and human types of Man mark stages in that course” (207). The working theory was that civilization could take the place of racial violence as a tool of “racial progress.” The conclusive activities of the Filipino war were vindicated by these exhibits. However the Black soldiers who served as “adjutants” in the Indian wars, the Spanish-American War, and the Philippine -American War were not allowed on the grounds in uniform.

In fact, African Americans were only represented at the Fair as actors on “the Old Plantation,” where they sang minstrel songs, staged a religious revival, and cakewalked. The music of Scott Joplin, who had composed a piece to accompany a waterfall called “The Cascades,” was banned from the grounds. Ragtime was considered a challenge to the beaux arts classicism that pervaded the Fair.

One memorable distinction between savagery and civilization was the rumor that the natives of the Philippine Reservation ate dogs. One of the neighborhoods near the exposition grounds is today known as”Dogtown,” because it was supposedly where the Filipinos got their dogs.

The theme song “Meet Me in St. Louis” made a salacious reference to dancing the “Hoochee-Koochee,” a reference to a dancer at the Columbian Exposition in 1893. Under the name “Fatima,” Fahreda Mazar Spyropoulos, danced so suggestively that she was banned from the St. Louis World’s Fair. The “hoochee koochee” was considered a “racially tinted sexual promise.” The subtext of the lyrics was a white woman lured by interracial desire and a white man who had lost control of his girl.

Walter Johnson concludes that two important lessons were established by the St. Louis World’s Fair.

- “to codify the history that had begun with Lewis and Clark–the history of nineteenth century St. Louis and the imperial project it sponsored–into a set of lessons that would guide the United States in the twentieth century.” e.g. President Roosevelt announced while touring the grounds that the United States “would reserve the right to intervene in the internal affairs of nations anywhere in the Western Hemisphere,” i.e. would become its “policeman.”(214).

- “It tried to channel all of the violence, steamy desire,, and brittle masculine anxiety that characterized both the history of the city and its daily life into a set of pat lessons about white supremacy and racial progress”( 215).