Change the narrative! That is what Bryan Stevenson called for, addressing the Road Scholar throng on Tuesday afternoon. That is what the “Conference on Civil Rights” is striving for. Perhaps he was speaking to the choir, but there was a sense that this choir could do more, with a refreshing of the music, and that’s why we were in Montgomery.

The Union won the Civil War, says Stevenson, but the South won the narrative war. Between 1865 and 1876 over 2000 blacks were killed, many by lynching. During the decades 1865 through 1901, Alabama revised its Constitution twice to reverse the effects of Congressional Reconstruction, as Steve Murray, Director of Alabama Archives and History, told us. They dismantled the State Board of Education and segregated the schools, they built restrictions on voting (poll tax, literacy tests, property ownership), and they centralized the government, so they could generally institute white supremacy.

Bryan Stevenson addresses the Road Scholars Tuesday afternoon.

Using primary documents, Murray showed how slavery fueled the exploding cotton production needs of the early nineteenth century and made a comeback in the late nineteenth century with the Convict Lease System, whereby prisoners were conscripted to back-breaking, dangerous labor. The prison workforce was swelled by inability of poor blacks to pay fines for minor infractions.

Using primary documents, Murray showed how slavery fueled the exploding cotton production needs of the early nineteenth century and made a comeback in the late nineteenth century with the Convict Lease System, whereby prisoners were conscripted to back-breaking, dangerous labor. The prison workforce was swelled by inability of poor blacks to pay fines for minor infractions.

White supremacists of the late nineteenth century referred to themselves as the “Bourbon Resurgence,” alluding to the wealthy interests that emerged still powerful after the French Revolution. Besides reviving the ranks of the Ku Klux Klan, they instituted social segregation of rail cars, cemeteries, public parks and libraries, and demonized inter-racial marriage.

Murray described the progress of racism as a pendulum that swung toward extremism in the Industrial Revolution (1760-1830), swung back toward reform following the Civil War (1865-1875), then swung back to Dejure Segregation and Slavery (through Convict Lease) (1875-1928), and swung again toward reform before and after World War II (1930-70). Where we are swinging now is a matter of conjecture.

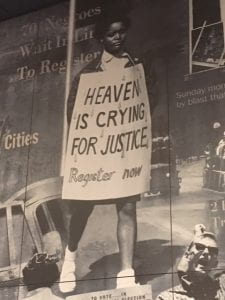

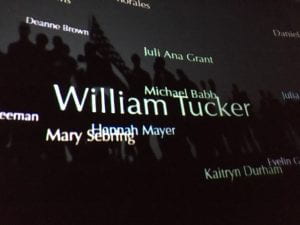

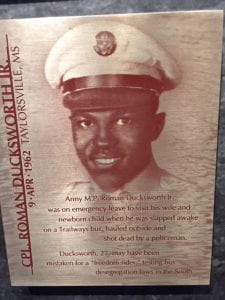

Stevenson emphasized the need to remember our history of racism, to state the truth, so we can reconcile and change the narrative. We responded to that charge by visiting two museums in Montgomery memorializing the martyrs and commemorating the heroes of racial struggle. The Civil Rights Memorial Center pictured forty victims of racial martyrdom in various media, including the unique disk of names swept by a continuous tide of water from its center, pouring over the edges. The wall behind it is inscribed by the biblical prophecy: “until justice rolls down like waters, and righteousness like a mighty stream.” The Wall of Tolerance is pictured below. You can add your name to the Wall if you pledge to fight for justice, equality, and human rights. From the example of the forty victims of racial terror, we are expected to take this pledge seriously. The corporal pictured below was sleeping on a bus when he was attacked and killed.

The Rosa Parks Museum is built near the bus stop where she was apprehended for refusing to give up her seat to a white person. The demonstration of her courageous stand comes through photographs, video, and a virtual reality performance of a crowded bus seen below. At this point you witness Ms. Parks about to be led away by a police officer. One of Bryan Stevenson’s anecdotes concerns an afternoon spent with her and two female companions. She admonished him about his overwork, he reported.

Tomorrow we motor to Tuskgegee to see the Airmen National Historic Site, the Tuskgegee Institute, the Tuskgegee Human and Civil Rights Multicultural Center , and the home of Booker T. Washington.

Thanks Bill for your nice summary of yesterday’s highlights!