Yesterday we heard about the “second slavery” in our country following the Civil War. Today we heard about the front line witnesses to the fight against racism and from the witnesses themselves.

In the ballroom of the Renaissance Hotel, Montgomery, Alabama, Dr. Dorothy Autry told us we were standing on “holy ground,” ground contested by heroes and “sheroes” in the early to mid-twentieth century.

In 1918 the NAACP took root in Montgomery and began to combat the literacy tests and poll taxes that excluded African Americans from voter registration. NAACP defended voting rights and attacked segregation in the courts till Brown vs. the Board of Education in 1954. Until the 1960’s NAACP was the undisputed champion of minority rights.

But the high point of the morning came when Dr. Autrey introduced heroes and daughters of heroes of the Montgomery Bus Boycott on a panel. We will not soon forget Hazel Gregory, represented by her daughter Janice Frasier (far right on the panel below). Hazel rescued the beaten Freedom Riders in Montgomery in May, 1961, driving their broken bodies to medical care. With the Women’s Political Council, she made thousands of copies of a call to boycott the buses, organized transportation, and raised $0.5 million to fund the boycott that lasted more than a year.

We will not forget Dr. Val Montgomery (second from right), who, when she was eight, lived in the peril of bombings and threatening mobs on Centennial Hill, where her family resided. They lived just a few doors from the parsonage where Dr. Martin Luther King lived. They witnessed the bombing of his home, and they protected the leadership of the Southern Christian Leadership Council by housing them for four days. She participated in the March on Washington and got expelled on the day of her high school graduation.

We will not forget Jean Gaetz (third from the right), wife of Rev. Robert Gaetz, a white pastor of a Black congregation in Montgomery. Their collaboration with the Bus Boycott and the Women’s Political Council earned them a bomb in their driveway, which was fortunately undetonated. Jean described her battle trying to forgive the seven bombers, who were caught, tried, and exonerated. Ultimately she realized that forgiveness was a gift to her and found surprising grace to laugh at the incident.

We toured the parsonage, where Dr. King spent the first six years of his ministry. He replaced a determined preacher, Vernon Johns, who spoke of the need for economic independence. Rev. King came to the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in 1954 and lasted until 1960, when his civil rights campaign took him to Atlanta. At the parsonage, we heard how he stood in his kitchen, just a few weeks before his house was bombed in December, 1955, and heard God’s promise to protect him and his family if he campaigned for justice and righteousness.

Probably the story of the Freedom Riders arriving in Montgomery and being attacked by a white throng of cab drivers was the most compelling narrative of race conflict. Dr. Bernard Lafayette was present at the Freedom Rides Museum to recount the night he was beaten and jailed, as one of the Freedom Riders, coming from Birmingham and going to Jackson MS. The job of the Freedom Riders was to verify that the anti-segregation laws were being executed along the route from Washington, D.C. to New Orleans, LA. Montgomery was not their first contact with violence., but Dr. Lafayette suffered three broken ribs there in an attack as soon as they got off the bus, and it was untreated in jail and all the way to Jackson, which he called their “beachhead.” When the Civil Rights attorneys arrived at the Montgomery jail with bond, they bailed out both the assailants and the Freedom Riders. Lafayette called it “agape love.”

He described the strategy of non-violence “saving the situation.” They would “not let a situation die,” meaning they engaged constantly with their adversaries. Even beaten and in jail with nothing but a few mattresses on the floor, they sang to the guards, “You can take away our mattresses, oh yeah,” when threatened. They sang with such harmony that the guards came in earlier looking for the radio making the sound.

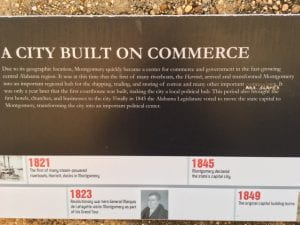

At the end of the day we visited the River Walk, where slaves were unloaded nearly two centuries ago. One of the historical markers by the tunnel from river to main street reads:

It was at this time that the first of many riverboats, the Harriet, arrived and transformed Montgomery into an important regional hub for the shipping , trading and storing of cotton and many other important commodities. with the grafitti “aka slaves”

Except for this unauthorized scribble, there is no mention of slaves in the eight plaques covering one hundred years of Montgomery’s history, the latter half marking the city as the hub of slave trading by the Civil War.