Too many of us experienced the Civil Rights Movement through a glass screen, as if in a galaxy far, far away. The journey to

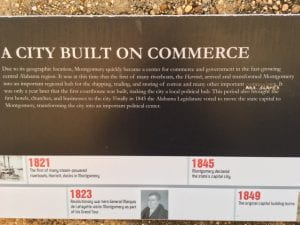

Alabama has proven the power of the eye-witness, over and over again, in Montgomery, in Tuskgegee, in Birmingham and finally in Selma.

Our story began today at the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma.

At Brown Chapel we met Joyce O’Neill and Diane Harris, teenagers at the time of the March, and later at Tabernacle Baptist, met the “foot soldiers” of the March, who recalled the early training of SNCC at Selma’s first mass meeting for voting rights May 14, 1963.

Brown Chapel

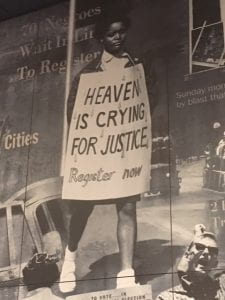

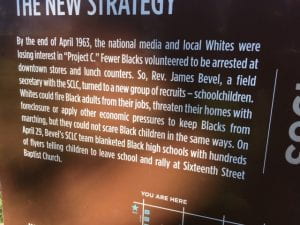

In spite of earnest efforts to register voters, only 2% of Selma’s black citizens were registered by 1965. Registration was blocked by harassment of applicants, by bizarre literacy requirements, by employers threatening to terminate Black employees for taking time off to register. The shooting of Jimmie Lee Jackson in Marion, February 26, 1965 climaxed the futile efforts, causing Rev. Jim Bevel to declare he was marching to Montgomery, and who would be going with him? https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Murder_of_Jimmie_Lee_Jackson

The plans to march from the Edmund Pettus Bridge to the Capitol Building in Montgomery were recounted through the eyes of Joyce O’Neil and Diane Harris for us at Brown Chapel. Joyce told how her sister, despite warnings from adults, followed the crowd to the bridge on “Bloody Sunday,” March 7, 1965, when marchers were chased off the bridge, with clubs and tear gas, by police on horseback right up the steps of the Chapel in pursuit of marchers. The story is told dramatically by the National Park Service documentary “Never Lose Sight of Freedom.”

Diane Harris recalled being arrested, as a teenager, on a protest march to the County Courthouse and taken to a prison camp outside of town. Later she was arrested a second time and taken to the National Guard Academy. She described how the “posse men” walked around the building, hitting boys with billy clubs and girls with cattle prods.

Side entrance of Tabernacle Baptist Church. The front is identical.

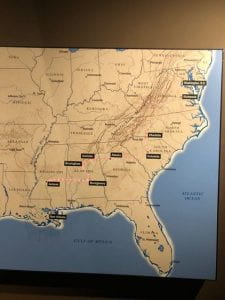

On March 21, 1965, 3200 marchers regrouped at Brown Chapel with the protection of federal troops to march to Montgomery. The march is chronicled at the Lowndes Interpretive Center located at the halfway point of the fifty-three mile trek. At the end of the first day they were told only 300 marchers could continue, to avoid blocking traffic on the narrow two-lane road. In spite of the warnings, cars and buses kept arriving with more marchers, so that some 10,000 marchers joined them by the fourth encampment at St. Jude’s Hospital outside Montgomery.

They arrived on the Capitol steps on March 25, 1965, where Martin Luther King gave his “Our God is Marching On” speech, punctuated at the end by “How long? Not long, because no lie can live forever. How long? Not long (etc.)” Then a recitation of “Mine Eyes Have Seen the Glory.” The entire demonstration and speech was staged for national television.

They arrived on the Capitol steps on March 25, 1965, where Martin Luther King gave his “Our God is Marching On” speech, punctuated at the end by “How long? Not long, because no lie can live forever. How long? Not long (etc.)” Then a recitation of “Mine Eyes Have Seen the Glory.” The entire demonstration and speech was staged for national television.

The Voting Rights Act was passed on August 6, 1965.

Interior Dexter Memorial Martin Luther King Baptist Church

Fifty-five years later we assembled at the foot of the Edmund Petus Bridge to re-enact the crossing. It was drizzling, as we marched two-by-two along the left footpath, following the pioneers of voting rights. We sang several verses of “We Shall Overcome,” and spanned the bridge in less than fifteen minutes. Some drivers passing over the bridge honked their approval.

At nightfall we were back in Montgomery, marching in the pouring rain up Dexter Avenue toward the Capitol Building. We had covered the most of the 53-mile trek to Montgomery by bus. After a day with Civil Rights history we were not about to complain about our inconvenient soaking. We sang a few more verses of “We Shall Overcome,” and the leadership had pity on us, detouring us into the Dexter Avenue Martin Luther King Memorial Baptist Church just short of our goal at the Capitol Building.

We heard Wanda Battle tell her personal conversion story and then urge us to follow through on the peace and justice work of Selma and Montgomery. What should we do with our new vision of Civil Rights history? “Charity begins at home,” she said, and then elaborated on the ultimately personal work of extending love to our neighbors. “Encourage and affirm others every day,” she urged, and she demonstrated with a few affirmations and hugs for members of our group. “Be genuine with yourself.” “Ask for grace to forgive.”

Dinner in the Alabama Activities Center across the street was never so welcome. We were still drying out when dessert was served. We sang a few verses of a song composed for us, “Bend the Arc Toward Justice” feeling hopeful, but tired.

We wobbled the final half mile to our hotel, mentally packing our bags and checking in for the rest of our trip home.

“How long? Not long!”